At 50, New City of Irvine is Evergreen

How Irvine was master-planned to be one of America’s most livable cities.

Everything was coming up green in the spring of 1970. In April, Americans would celebrate the first Earth Day, marking the dawn of the global environmental movement. In Washington, the White House was finalizing plans for a new Environmental Protection Agency and Clean Air Act. General Motors had just promised “pollution-free cars” by 1980. And 50 miles south of Los Angeles, Irvine Company executives were unfurling plans for a brand-new, green city.

The City of Irvine was rigorously designed to be the heart of an environment “where nature and man both prosper,” as the Company announced in an enthusiastic press release on March 19, 1970. The blueprint delivered that day to Orange County planners included an unusual promise: Irvine residents “will live in an environment that is as attractive, as balanced and as enduring as the science of urban planning can make it.”

This was a striking commitment even in the context of that era’s green ambitions. Yet it arose from a singular set of circumstances. A single corporation held claim to 93,000 acres of undeveloped land – six times the size of Manhattan – and had determined to maintain control of it, master-planning its development.

Irvine was neither the first nor the largest modern city to be designed from the ground up. More than two centuries earlier, Washington, D.C., was planned by the French former revolutionary fighter Pierre Charles L’Enfant. Brasilia, Brazil’s brand-new, master-planned capital, was inaugurated in 1960.

And in 1964, while Irvine was still on the drawing board, the small, woodsy town of Reston, Virginia, planned by a New York developer, would become known as a pioneering effort to avoid the miseries of suburban sprawl.

Still, Irvine was special in one major way. Its fortune in having a single owner for the city’s land and its natural surroundings would pave the way for a long-lasting and mutually rewarding collaboration between a private company and local City Council members.

On Dec. 28, 1971, Irvine’s 10,000 inhabitants embraced their good luck, overwhelmingly voting to incorporate as a new city.

The Founding Father

Irvine is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. But the city’s unique history began more than 100 years earlier.

In 1846, James Irvine, then an impoverished 19-year-old immigrant, arrived in New York, fleeing the Irish potato famine. After making his way to San Francisco, he sold food and provisions to gold rush miners and made his fortune by investing in real estate. At age 37, Irvine headed to Southern California, where he discovered what he called the “most delightful” land he had ever seen, in or out of the state. The Irvine Company dates its start from 1864, when Irvine and two partners, whom he later bought out, began acquiring vast tracts of former Spanish and Mexican land grants. These would include the 93,000-acre Irvine Ranch, today just an hour’s drive south of downtown Los Angeles.

Priceless, Pristine Land

Thanks to a long line of conscientious stewards, much of the land that first enchanted James Irvine more than 150 years ago still looks a lot like it did then. Descendants of the eagles, hawks, mountain lions, badgers and scores of species of butterflies that Irvine saw on his first horseback forays still make the Ranch their home.

The Ranch stretches for 9 miles along the Pacific Coast and 22 miles inland to the Cleveland National Forest. Its landscapes are as varied as they are often visually stunning, ranging from remote canyons and mountain watersheds to grasslands, oak woodlands, coves and beaches. Its ecological treasures include one of Southern California’s largest coastal freshwater marshes and the 5,500-acre Limestone Canyon, home to a striking geological formation called the “Sinks,” sometimes compared to a miniature Grand Canyon.

The Ranch belongs to one of the world’s few regions with a Mediterranean climate of mild winters and warm summers. Scientists have distinguished the area as one of 36 biodiversity “hot spots” due to its wealth of rare and vulnerable plant and animal species. The list of flora and fauna endemic to this corner of the continent includes Tecate cypress trees, the Nutall’s woodpecker and the endangered California gnatcatcher, a songbird that lives in coastal sage scrub.

The Ranch property encompasses roughly one-fifth of modern Orange County, home to more than 3 million people and many more millions of yearly visitors, drawn by attractions including Disneyland and some of the world’s most beautiful beaches. The Irvine Company initially used the land to raise cattle and sheep but later expanded into agriculture. By 1910, the Ranch was the most productive agricultural location in California, expanding into crops, including oranges, cauliflower and grapes.

Still, the land had a much more unusual destiny in store.

A Struggle to Stop Smog and Sprawl

By the 1950s, the outside world was starting to intrude on James Irvine’s paradise. Marines and other members of the military from all over the country who had been trained or stationed in Southern California during World War II had fallen in love with the climate and scenery and brought their families west to start new lives. A frenzy of freeway building made it easier for those with jobs in Los Angeles to commute to homes near forests and fresh air. But now, in many parts of the region, smog and traffic had reached appalling levels. From 1950 to 1987, Orange County’s population multiplied tenfold, from roughly 200,000 to more than 2 million. Urban sprawl from the north and west was approaching like “oozing molasses,” in the words of one Irvine Company executive.

The rapidly growing population put pressure on the Company to subdivide and sell off its properties. Surrounding cities, including Newport Beach and Santa Ana, sought to annex some of the land. The Company resisted, seeking an alternative solution. It found one in 1959, thanks to an already-celebrated architect named William Pereira. University of California regents had hired Pereira to find a site for a new campus. He took them on a tour of 23 sites, ending with the one he liked best: The Irvine Ranch. Pereira already had a larger plan in mind. He envisioned a 1,000-acre university within a “city of intellect,” free from “the tragedies of helter-skelter planning, of the impossible traffic, the sprawling disorganization” he had seen all over California. He proposed creating a series of master-planned villages where resident families would be able to walk to schools and shopping, leaving their cars in their garages.

Architecture critic Alan Hess, who was such a fan of Irvine’s Master Plan that he made his home here in 2004, would call it the “largest, most successful application of important progressive planning ideas since 1900.”

The Irvine Company embraced Pereira’s concept, and in September 1960 transferred title to 1,000 acres to the UC system for a symbolic fee of $1, a gesture required by the terms of the Company’s charter. The land sale marked a fundamental change for the Company, requiring it to be “proactive rather than reactive in the Ranch’s transformation from its agricultural past to its urban future,” as one executive expressed it. In the process, the Company assumed a new long-term role as “Master Community Builder.”

Three years later, as the bulldozers, graders and carpenters went to work, Time magazine put Pereira’s portrait on its cover, a distinction shared that year by the likes of Muhammad Ali and Robert Kennedy. The magazine praised Pereira for his “early environmental awareness.” The architect understood that the new city had to be a financial success, but also hoped it would serve as a model for a more civilized lifestyle, with more respect for nature than U.S. suburbs had yet produced.

A Blueprint for a Green Utopia

Irvine Company planners shared Pereira’s hope of combatting what one of them called “a crisis of the spirit” in American suburbs.

“In the smaller towns, monotony is king. In the larger cities, the scattering of major community facilities has created an urban sprawl with which it is impossible for any man to identify,” the 1970 press release said.

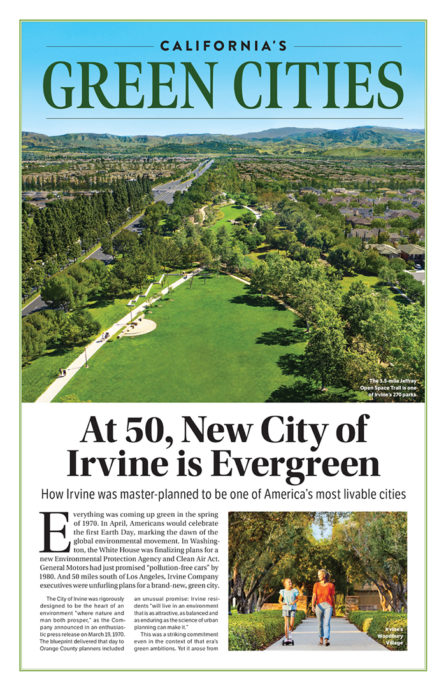

The new city would be “totally master-planned,” from its roads to its utilities to its homes, factories and schools, anticipating needs more than 30 years in the future. Its hub would be the campus of the new University of California, Irvine, with spokes extending into the surrounding residential area. Irvine’s most distinctive characteristic would be self-contained residential “villages” linked by forested corridors. This would greatly reduce dependence on cars, as Pereira envisioned, because within a 10-minute walk along a greenbelt, residents could reach destinations including an elementary school, playground, recreation center and community pools. At maximum, they would walk 15 minutes to reach a shopping center with a market, restaurants, hardware store, banks and barbershop.

Architecture critic Alan Hess, who was such a fan of Irvine’s Master Plan that he made his home here in 2004, would call it the “largest, most successful application of important progressive planning ideas since 1900.” Many other future residents just liked what they saw: a distinctively family-friendly and environmentally smart city. In September 1976, more than 7,000 prospective buyers competed in a lottery for the first 221 homes for sale in the new village of Woodbridge.

A Deeper Shade of Green

The next four decades would bring more transformational change for both the Irvine Company and The Irvine Ranch. Under the guidance of Donald Bren, elected Chairman of the Board in 1983 and who later became the majority owner, the Company donated more than half of its original land holdings – nearly 60,000 acres – for permanent conservation.

The next four decades would bring more transformational change for both the Irvine Company and The Irvine Ranch. Under the guidance of Donald Bren, elected Chairman of the Board in 1983 and who later became the majority owner, the Company donated more than half of its original land holdings – nearly 60,000 acres – for permanent conservation.

An avid outdoorsman, Bren values the Ranch both for its beauty and recreational opportunities for Irvine residents and for its scientific importance – including the opportunity to leave entire habitats intact.

“For many years, I have walked, hiked, biked and ridden the trails and wilderness lands of this Ranch,” he says. “They are very close to my heart, my home, and they represent freedom for everyone, as well as for the natural species that have made their home here for centuries.”

Bren has repeatedly said that he wants the Ranch to “be known and celebrated as much for what is NOT developed here,” and has pursued that goal with a series of major decisions that would protect large, intact ecosystems.

The first big grant came in July 1996, when the Irvine Company contributed 21,000 acres to a new 37,000-acre land preserve. The plan relied on a previously untested California state law, the Natural Community Conservation Planning Act, designed to protect species by safeguarding large parts of their habitats. The preserve would not only protect 39 rare plant and animal species but would guarantee Irvine and Orange County residents easy access to enjoy the wilderness, even while living in one of the great metropolitan areas of the United States.

Eventually, more than 40 other California cities would follow this lead, using the NCCP Act to set aside 1.5 million acres as nature reserves, with pending applications to preserve millions of acres more.

In 2001, the Company donated another 11,000 acres of undeveloped land, including an important wildlife corridor, for permanent protection. Then in 2010, a final gift of 20,000 acres was transferred to Orange County – and permanent public ownership – bringing the total to more than 57,500 acres, or nearly 60% of James Irvine’s original holdings.

State and federal officials applauded these developments.

In 2006, The Irvine Ranch was designated a United States National Natural Landmark, and two years later the ranchland was recognized as a California State Natural Landmark.

Still, Irvine Company leaders felt obliged to do more than simply hand over property. They also wanted to help guarantee that the land would remain unspoiled, even as Irvine residents would have use of it.

“Urban planners from all over the world have come to study, and often to try to copy, Irvine’s success. What I see increasingly are places like Irvine, but none are quite as evolved.” –Sustainability Expert Joel Kotkin

That’s what led to the creation in 2005 of the nonprofit Irvine Ranch Conservancy, supported with a $50 million contribution from the Donald Bren Foundation.

Before launching the new conservancy, the Irvine Company took care to study similar, successful ventures, including the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy and Catalina Island Conservancy. It also recruited board members from those organizations and hired as its founding executive director Michael O’Connell, a veteran conservation scientist who had held senior positions with the Nature Conservancy and World Wildlife Fund. The new conservancy was tasked with using the best scientific practices to make the preserve a model of excellent private-public management of urban wilderness, balancing conservation with opportunities for recreation. O’Connell quickly got to work, orchestrating the removal of invasive plants, the restoration of wetlands and the creation of hundreds of miles of trails, including a new 22-mile bike path from the mountains to the sea.

Board Chairman Bren has referred to Irvine’s gifts of open space as “an investment in the future.” The value of the assets involved remain uncalculated in financial terms, but it’s fair to say it’s growing every day.

In 1981, Stanford biologists Paul and Anne Ehrlich introduced the term “ecosystem services” to refer to the often-unrecognized economic benefits of pristine nature. Forests, for instance, perform valuable work by cleaning the air; mangrove trees protect homes from storms; and undeveloped land of all kinds provides opportunities for people to restore themselves by enjoying nature. As the world’s supply of undeveloped land rapidly shrinks, environmentalists and economists are still struggling to come up with ways to monetize trees that aren’t made into timber and wetlands that help prevent flooding as long as they stay undeveloped.

One day these “services” may finally be recognized as bulwarks of our economy. O’Connell, the conservancy executive director, sees this value daily. “I can’t even begin to guess what the value of this property is. But in terms of its biological and geologic value, it is truly priceless. It’s like having a national park in our backyard,” O’Connell told the Los Angeles Times.

A Bright and Sustainable Future

As Irvine turns 50, many of its early ambitious dreams have come true. The campus at the heart of the “city of intellect” has become a world-class research center and has been ranked a top 10 public university by U.S. News & World Report.

As Irvine turns 50, many of its early ambitious dreams have come true. The campus at the heart of the “city of intellect” has become a world-class research center and has been ranked a top 10 public university by U.S. News & World Report.

Irvine’s K-12 public schools are among the best in the nation, winning both the National Blue Ribbon award and the California Distinguished Schools/Gold Ribbon designation.

The City of Irvine has also built a national reputation for environmental leadership. In 1989, it was the first in the nation to restrict the use of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons. Among U.S. cities, Irvine also has one of the highest percentages of solar-powered homes and has attracted some of the nation’s leading engineers developing electric-vehicle batteries and engines. The Irvine Company itself continues to be an environmental innovator: In 2018, it completed the world’s first fleet of hybrid-electric buildings, featuring state-of-the-art Tesla Powerpack battery systems at 21 high-rise office buildings.

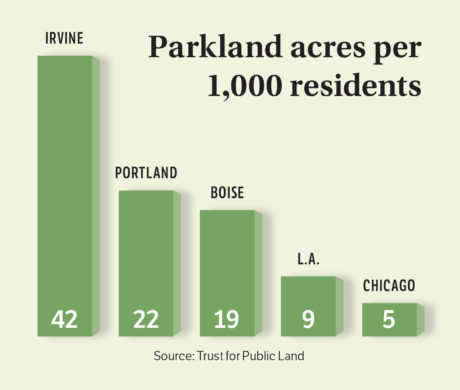

Thanks, in good measure, to its exceptional Master Plan and deep-green sensibility, Irvine has achieved a balanced climate, in which residents benefit from accessible and enjoyable open space, clean water and spacious parks.

“You think of what makes a city green and sustainable – it’s creating a community that residents can enjoy today while ensuring that future residents will be able to enjoy it even more so.” –Irvine Mayor Farrah Khan

Irvine has retained its special character of villages accessible by roads, walkways and bike-paths, and homes designed to take maximum advantage of views of the surrounding, conserved nature. It’s just part of what has distinguished the city, by many accounts, as one of America’s best places to live. Irvine’s population remains unusually manageable at below 290,000, much smaller than the Plan’s target of 430,000 residents by the year 2001. CNNMoney.com has ranked Irvine among America’s top cities to live in, while the federal government has repeatedly reported it to have the lowest per-capita rate of violent crime of any other city of its size.

Urban planners from all over the world have come to study, and often to try to copy, Irvine’s success, according to sustainability expert Joel Kotkin, Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University. “What I see increasingly are places like Irvine, but none are quite as evolved,” Kotkin said.

Irvine’s coveted status as one of America’s greenest cities continues to be its greatest gift to residents. It’s truly a small miracle, owing to 50 years of careful planning and ambitious environmental stewardship, that nearly 300,000 Irvine residents living in one of the most populated corners of the United States still need travel less than 20 minutes to enjoy a majestic national park.

“I couldn’t be prouder of all that the City of Irvine has accomplished over the last 50 years, and I am even more excited about what’s to come in the next 50 years,” said Irvine Mayor Farrah Khan. “You think of what makes a city green and sustainable – it’s creating a community that residents can enjoy today while ensuring that future residents will be able to enjoy it even more so. It’s creating a legacy that will endure for generations to come.”